Felony Disenfranchisement

Keeney, Carolyn. usstates.jpg. 2000. Pics4Learning. 4 Mar 2016

During this election season there will be many issues that will be debated from gun control, immigration, gay marriage, etc. However, there is still a big issue that affects millions of adults across the country and that is felony disenfranchisement. Felony disenfranchisement is excluding those who would otherwise be eligible for voting, but have committed a felony and therefore not allowed to vote. A felony is a more serious crime such as murder and domestic violence, but it can also be a weapons violation or forgery and counterfeiting.

In America, felony disenfranchisement is a matter on the state level and not on the federal level. This comes from a specific part in Section two of the 14th amendment, which indicates that if a state tries to deny vote for those eligible, “except for participation in rebellion, or other crime,” it will suffer a loss in representation.

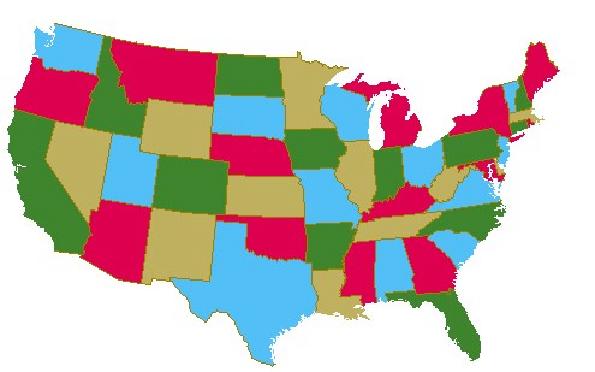

The 50 states, plus the District of Columbia, have different laws on felon voting. In two states, Maine and Vermont, convicted felons are allowed to vote even while they are in prison and do so by absentee ballot. In 14 states, including Pennsylvania, Illinois, and D.C., felons are allowed to vote after they finish their term of incarceration. For the four states, California, Colorado, Connecticut, and New York, felons are allowed to vote after serving their term of incarceration and parole as well. In 19 states, including Georgia, New Jersey, and Missouri, felons have to serve their term of incarceration, parole, and probation just to vote again. In 11 states, such as Florida, Mississippi, and Virginia, a felon could lose their vote permanently.

In the states that you could lose the vote permanently in, each have different variations of how they go about felony disenfranchisement.

In Mississippi, a felon can regain the right to vote, but has to go their state representative and convince them personally to write a bill that restores the right for them to vote again. That bill will then have to go through both houses of the legislature for the felon to vote again. The governor of Mississippi can also grant re-enfranchisement to the individual. In Florida, a felon has to wait five years before applying for Executive Clemency and if a felon has committed certain felonies, such as murder, drug trafficking, child abuse, etc. they will have to wait seven years to see if their vote is restored. In Virginia, a felon who committed a non-violent crime will get their right to vote back after serving term of incarceration, paying all court costs, fines and any restitution.

This issue has been hotly debated before in previous years. In 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court made a big decision in the case of Richardson v. Ramirez. The Court decided that the state of California did not violate the Equal Protection Clause by disenfranchising convicted felons who had completed their sentences and paroles. The Equal Protection Clause is at the end of Section one of the 14th amendment and says that no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” In 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Hunter v. Underwood that the states do have the right to disenfranchise criminals, but “not with a racially discriminatory intent.”

The debate over felony disenfranchisement doesn’t just stop at the Supreme Court, many regular American citizens have argued over allowing or not allowing felons to vote. One of the first things that people point to when arguing their side on this issue is the Constitution. Those for felony disenfranchisement point to Section two of the 14th Amendment as the endorsement for their view and those against it point out the 8th Amendment, which is against “excessive” sanctions and “punishment for the crime should be graduated and proportioned to the offense.” (Weems v. United States) It is also debated whether a felon should be trusted enough to vote. Those against felon voting believe that since we don’t allow children or aliens (legal and illegal) to vote, there shouldn’t be a reason to allow felons to vote as they are untrustworthy people. Those for felon voting say that if we let felons have their right to practice religion and have free speech that not allowing felons to vote would go against an American citizen’s civil liberties. Other topics people argue over are felon voting in jail, automatic restoration of vote, social contract theory, etc.

The most contentious argument on felon voting is over race. There are many people who believe that race is a major issue for felons not being allowed to vote. The Sentencing Project states that on estimate that around 5.85 million people are not allowed to vote in the United States due to felony disenfranchisement. A majority of the people in prisons now and in recent years are, Blacks and Latinos. Prison Policy Initiative found that although Blacks are only 13% of the U.S. population, they are 40% of the prison population and Latinos are 16% of the U.S. population, but are 19% of the prison population. The U.S. Census also found out that Blacks are incarcerated five times more than Whites and Latinos nearly twice more. Those that use race in the debate say that the reason for felon disenfranchisement is that certain politicians, particularly Republicans, want to stop these people from voting so that they don’t vote against them. Support from this has been used in two studies from New York and New Mexico. In New York, it was shown that ex-felons that are registered are mainly registered democrat at 61.5%. In New Mexico, registered ex-felons were 51.9% democrat.

They have argued that this tactic is just a reminder of the pre-Voting Rights Act era of Segregation when it was incredibly difficult for Blacks in America to vote. They have also pointed out on how the “War on Drugs” has made it even more appealing for those politicians to ensure that felony disenfranchisement stays in place.

It has also been argued that the Constitution doesn’t necessarily specify that felony disenfranchisement should be a must for the states to have. For instance, when those for felony disenfranchisement use Section two of the 14th Amendment for support of their view, those against it say that particular Section was put in place to stop people from still supporting the Confederacy when they joined the Union, and not to disenfranchise felons. The 15th Amendment is another argument against felony disenfranchisement. The 15th Amendment states that, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Since those who believe that the prison system has a disproportionate number of Blacks and Latinos, felony disenfranchisement is a violation of the 15th Amendment as it restricts the votes of those races. Those that are against the use of race in the debate say that felony disenfranchisement isn’t meant to discriminate against one race more than the other. They believe that felons have to assimilate back into society and have to learn new things about life before they can earn their suffrage again. However, the concession that many of those who support felony disenfranchisement will make is that any voting law that discriminates against race should be unconstitutional.

There have been many people who have spoken up on both sides of the debate. Former United States Attorney General Eric Holder voiced his disapproval of felony disenfranchisement as he says that these laws have been used “to strip African Americans of their most fundamental rights.” He also pointed out that, “Throughout America, 2.2 million black citizens – or nearly one in 13 African-American adults – are banned from voting because of these laws.”

A supporter of felony disenfranchisement is Attorney General of Florida, Pamela Bondi, who has defended her state’s version of felony disenfranchisement against accusations of racism. She claimed that the state’s five year waiting period for restoration to vote doesn’t “have anything to do with race.” She also strengthened her stance by using the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruling on her laws, which said that, “The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals examined the historical record and soundly rejected the argument that Florida’s prohibition on felon voting was originally motivated by racial discrimination.”

Regardless of what position an individual will take on this issue, there are still many questions as to whether felony disenfranchisement should continue or not. The debate centers on many issues, but the most important issue should be whether felony disenfranchisement is truly ruining voting representation or if it is helping this country by not allowing those who have committed crimes that should disallow them from voting for a certain period of time or longer. Although this issue is not being talked about much by both parties, it would be good to find out each of the candidates’ views on felony disenfranchisement and how it should be carried out in this country.